What makes me unique if we all look alike?

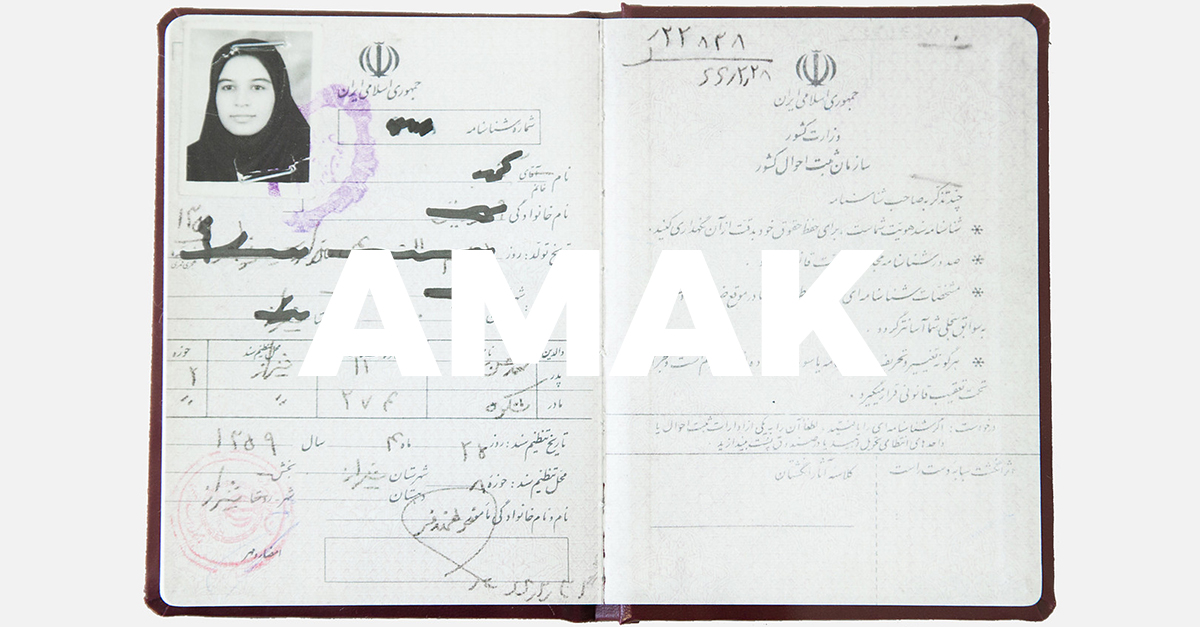

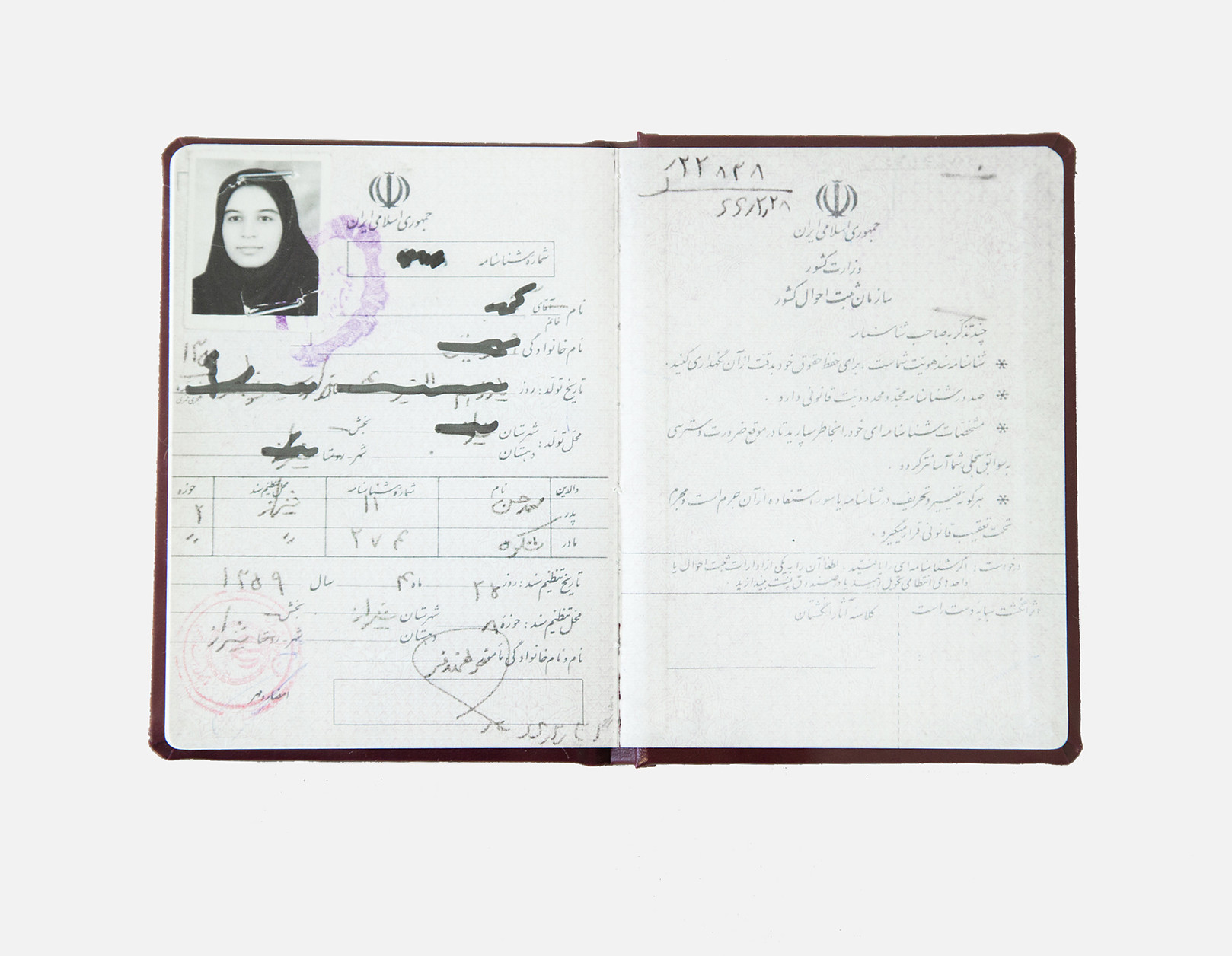

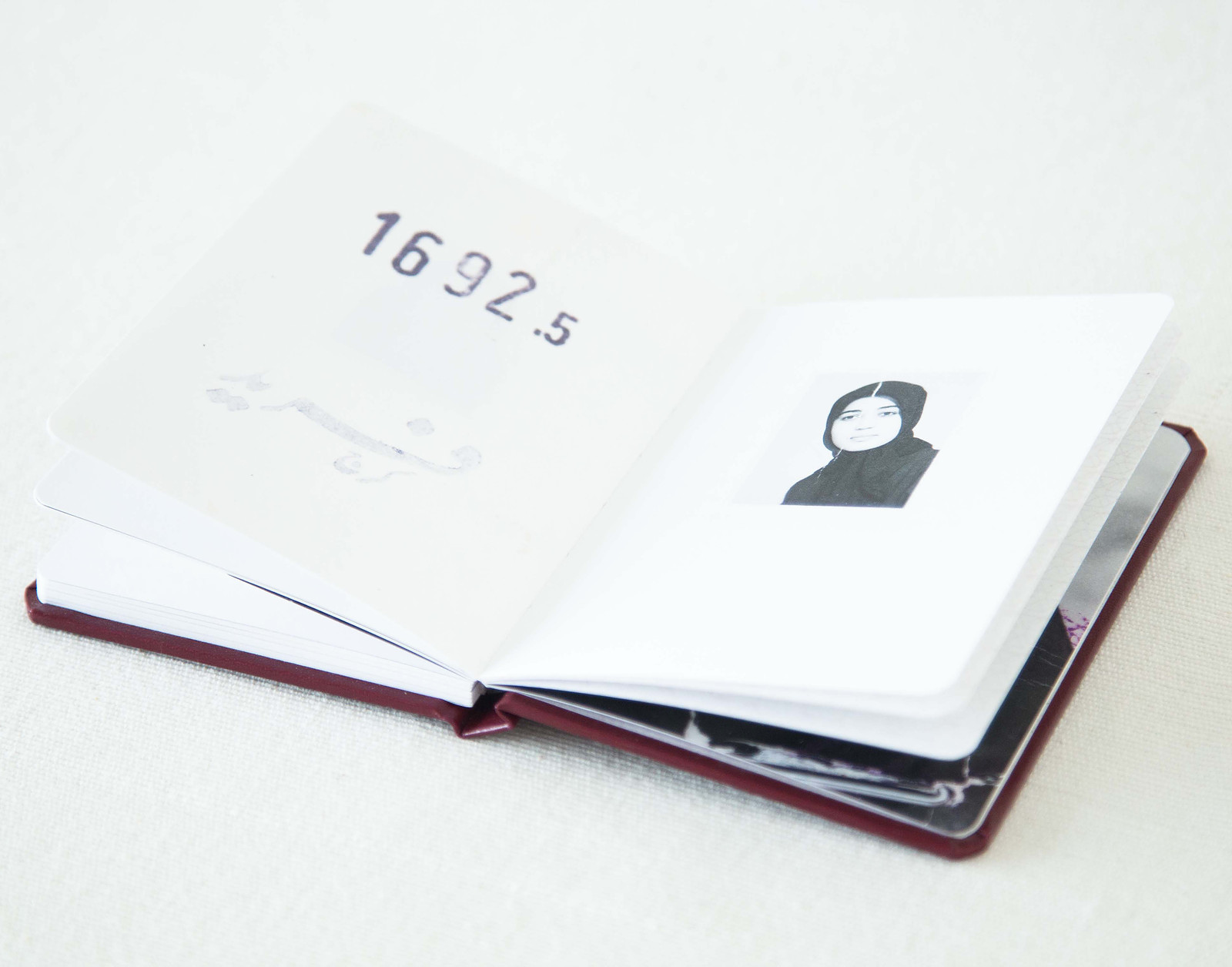

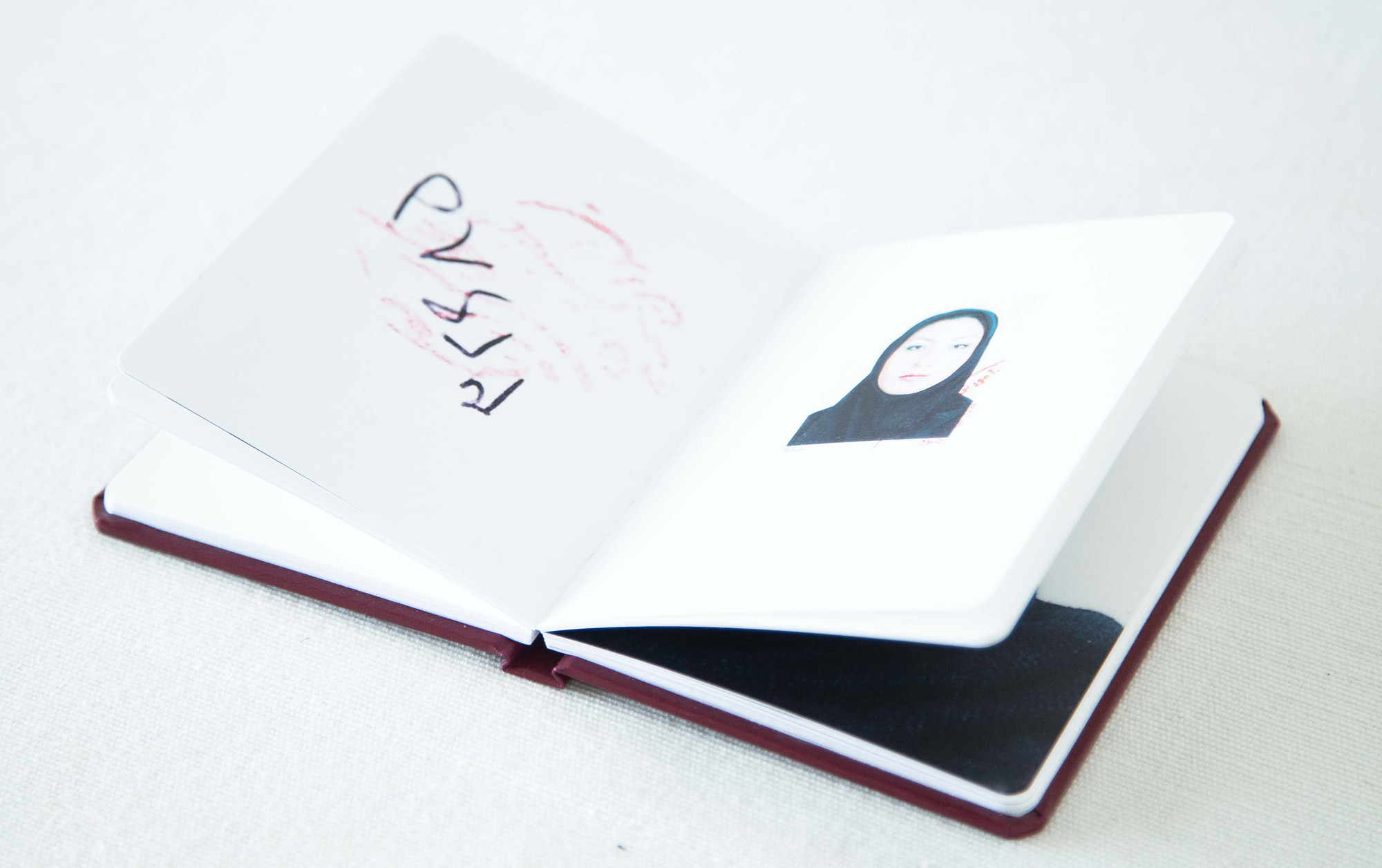

[ENGLISH VERSION] All Iranian women look the same in their Shenasnameh photos. The Shenasnameh is the name of the official Birth Certificate in Iran, and the regulations established by the government for the portrait that every Iranian woman have to provide are very strict. In response, Amak Mahmoodian created another Shenasnameh, for which she gathered her portrait, her fingerprint, and those of other women together. Put side by side, the photos reveal their differences and personality traits. Through this book Amak highlights the singularities of Iranian women.

How is your work “Shenasnameh” born?

Seven years ago, I was waiting in a reception room, holding my birth certificate and the birth certificate of my mother. My eyes began to move back and forth between her photo and my photo. I suddenly realized what these images meant, what they showed, and what they didn’t show. My mother and I, despite all our differences, were welded together into one being. I looked like my mother, and my mother looked like me, but this resemblance went well beyond a family resemblance. I became aware that all Iranian women were being restricted to look the same, like us: plain faces under hairless scarves.

The same day my fingerprint was fixed next to my image, and my mother’s fingerprint next to her image. Though we had similar faces, our fingerprints were different.

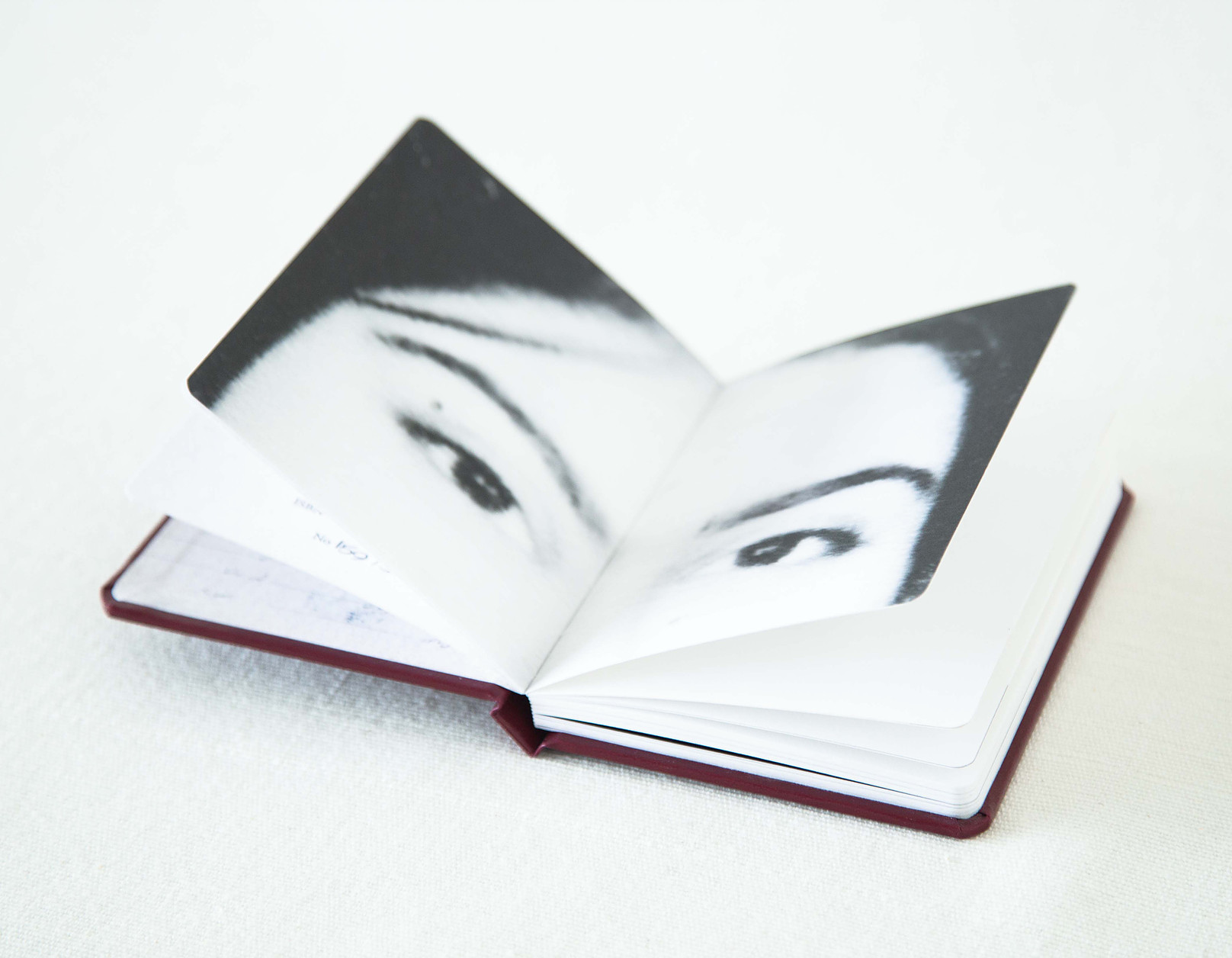

After that I started collecting Shenasnameh portraits and fingerprints of Iranian women: relatives, friends and women I didn’t know. Different stories began to be told and their differences became visible. By a glint in the eyes, a lip contour, or a raise of the eyebrows, these women were still asserting their individualities. “Shenasnameh” is about these women who are individuals, who are more than just a loose strand of hair.

What are the regulations for these portraits?

After age 9, women’s hair must be covered with a scarf, and any excess of make-up will be met with official disapproval. A Shenasnameh is valid for life, but the photograph must be updated according to the standards, and you have to personally bear the costs.

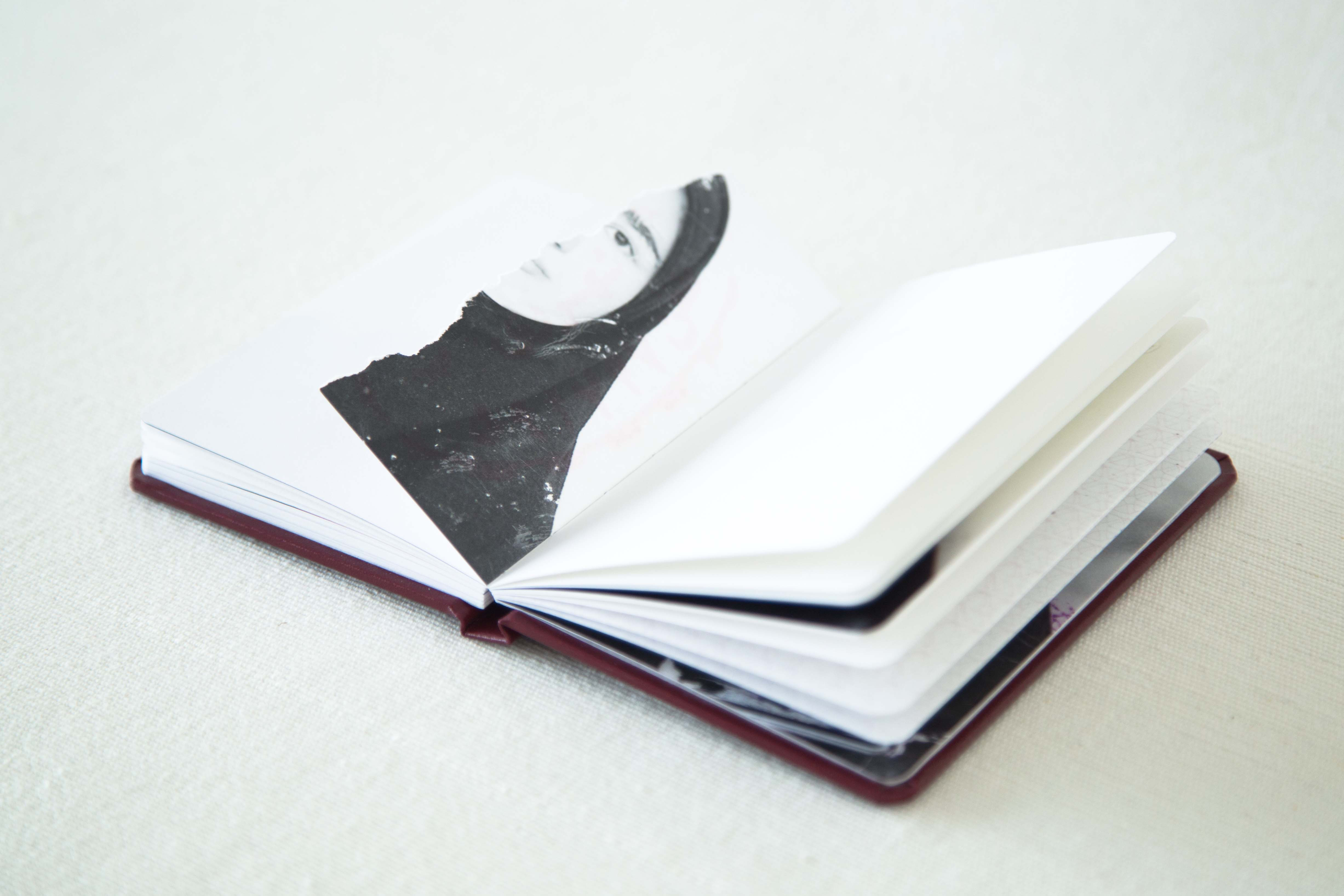

There is one torn up photograph in your project. Does this image have a particular story?

The torn photograph just came to me. I found it a Wednesday afternoon while I was walking in the street. I was working very hard on this project at that time, and I was feeling it with my whole being. I took the photo home and aligned it with the others.

Even if we can only see half of her face, the image is telling us her story: she self-censored herself before abandoning her photograph, so she couldn’t be identified by other people.

Does the fact that you are an Iranian woman made the collecte easier?

Well, yes. To present the project to these women, I showed them my Birth Certificate photo. Collecting the photos and the fingerprints was a journey, inside and literally. “Shenasnameh” is the story of my own life because I’m one of these women. I feel their stories as if they were my own story because I lived with them for years. They trust me and I respect them.

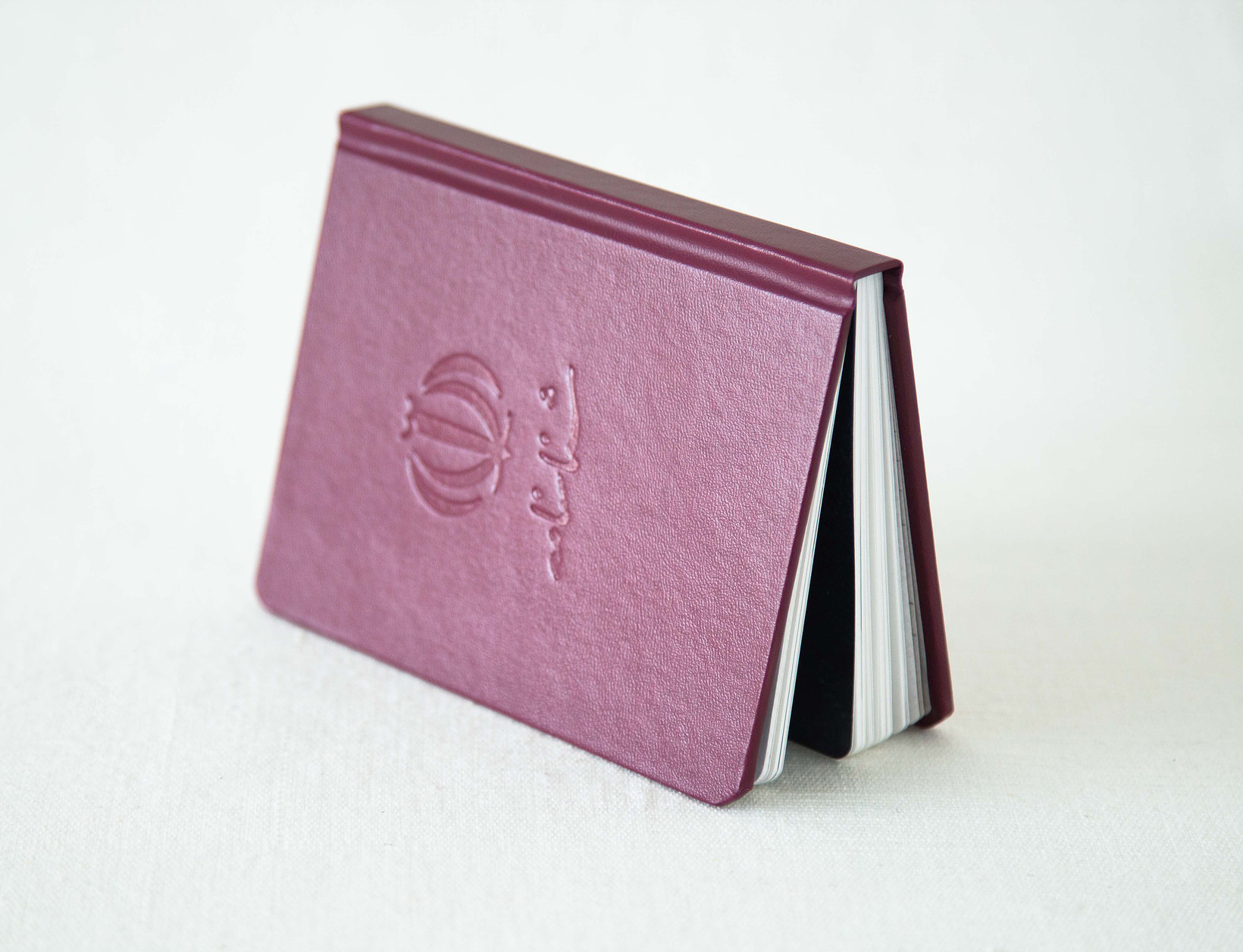

So this book expresses something personal pertaining to a general issue. Each chapter of the book is a chapter of my life. Furthermore, the black fabric covering the book is the same fabric with which I covered my hair with for years. It is part of my memories, it covers my memories.

► Photography, © Amak Mahmoodian. Amak Mahmoodian is an Iranian photographer, film maker and curator living in the UK. She was born in Shiraz, Iran, in 1980. Visit her website to discover her work.

[VERSION FRANÇAISE] Toute les femmes se ressemblent sur les photos de leur Shenasnameh, le certificat de naissance officiel en Iran. Partant de ce constat, Amak Mahmoodian a crée un Shenasnameh un peu atypique : on y trouve son portrait, son empreinte digitale et ceux d’autres femmes iraniennes. Mises côte à côte, les photos dévoilent les différences et traits de personnalités que les normes esthétiques fixées par le gouvernement ne peuvent effacer. À travers ce livre, Amak célèbre les singularités des femmes d’Iran.

Comment as-tu commencé ton travail « Shenasnameh » ?

Il y a sept ans, j’attendais dans une salle de réception avec, entre mes mains, mon certificat de naissance et celui de ma mère. Mes yeux ont alors commencé à faire des allers-retours entre la photo de ma mère et la mienne, et j’ai soudainement pris conscience de ce que ces images signifiaient, de ce qu’elles montraient et de ce qu’elles ne montraient pas. Ma mère et moi, malgré toutes nos différences, nous étions comme soudées en un seul être. Je ressemblais à ma mère, et ma mère me ressemblait. Mais cela allait bien au-delà d’une simple ressemblance de famille. J’ai réalisé que toutes les femmes iraniennes étaient restreintes à la même apparence, comme nous ; Des visages lisses sous des voiles ne laissant entrevoir aucun cheveu.

Le jour même, mon empreinte digitale fut fixée à côté de mon image, et l’empreinte de ma mère à côté de son image. Bien que nos visages étaient devenus les mêmes, nos empreintes digitales étaient différentes.

Après ce jour-là, j’ai commencé à collectionner les portraits officiels d’autres femmes iraniennes, ainsi que leurs empreintes digitales : de membres de ma famille, d’amies, et de femmes que je ne connaissais pas. Peu à peu, de nombreuses histoires ont commencé à être racontées et les différences sont devenues perceptibles. Par un reflet dans les yeux, un contour de lèvres, ou une hausse des sourcils, elles affirmaient encore et toujours ce qui les rendait uniques. « Shenasnameh » parle de ces femmes qui sont des individus, qui sont bien plus qu’un simple brin de cheveux.

Quelles sont les normes gouvernementales iraniennes concernant les photos d’identité des femmes ?

Dès 9 ans, les cheveux des femmes doivent être couverts par un voile, et tout excès de maquillage fait face à une désapprobation officielle. Bien que le Shenasnameh est valable à vie, la photo doit être mise à jour si jamais les normes changent, et c’est à vous de prendre personnellement en charge ces frais.

Il y a une photo d’identité déchirée dans ton projet. Cette image a-t-elle une histoire particulière ?

La photographie déchirée est venue à moi d’elle-même. Je l’ai trouvé alors que je me promenais dans la rue, un mercredi après-midi. C’était à la période où je travaillais intensivement sur ce projet, et il ne me sortait jamais de l’esprit. Je l’ai ramené à la maison et l’ai aligné avec les autres.

On y voit plus que la moitié de son visage, mais cette image nous raconte son histoire : celle d’une femme qui s’est censurée elle-même avant d’abandonner sa photo pour ne pas être identifiée par d’autres personnes.

Est-ce que le fait que tu sois une femme iranienne a facilité la collecte ?

Effectivement, pour présenter ce projet à ces femmes, je commençais d’abord par leur montrer ma propre photo. Cette collecte des photos fut à la fois un voyage intérieur et extérieur. « Shenasnameh » est le récit de ma propre vie, car je suis une de ces femmes. Je ressens leurs histoires comme si elles étaient la mienne car j’ai vécu avec elles pendant des années. Elles m’ont fait confiance et je les respecte.

Ce livre exprime donc quelque chose de personnel se rapportant à une problématique générale. Je considère chaque chapitre de ce livre comme un chapitre de ma vie. Et le tissu noir qui couvre le livre est le même tissu avec lequel j’ai couvert mes cheveux des années durant. Il fait partie de mes souvenirs et les couvre en même temps.

► Toutes les photos, © Amak Mahmoodian. Amak Mahmoodian est une photographe, réalisatrice et curatrice iranienne vivant au Royaume-Uni. Elle est née en 1980 à Shiraz, en Iran. Vous pouvez découvrir ses travaux sur son site : amakmahmoodian.co.uk.